The U.S. is in the midst of a caretaking crisis. More older adults are living longer, and due to rising health care costs and a lack of retirement savings, they cannot afford long-term care. Experts say that’s why the Biden administration has announced plans to address these concerns by bolstering aid to older adults and disabled Americans.

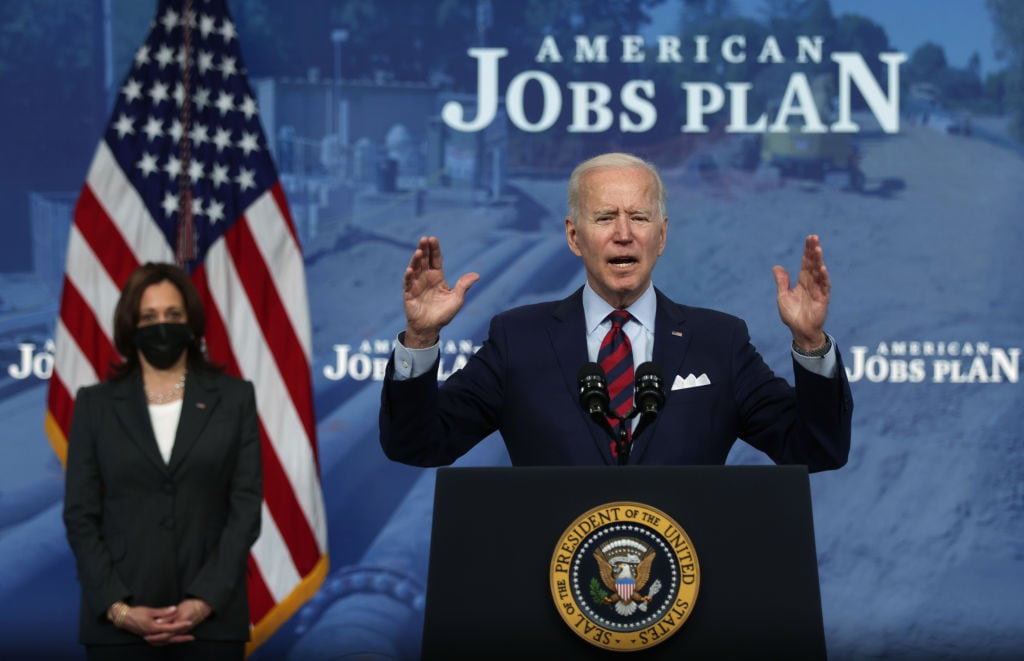

President Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan, also referred to as the infrastructure plan, proposes an allotment of $400 billion to expanding caretaking services, including Medicaid-based home care and access to higher quality home care professionals.

The current language of the plan could potentially lead to big savings for low-income families seeking long-term care. Still, it bears noting that the jury is out on the specifics of how exactly the proposals might actually be set into motion. For example, Medicaid, the primary focus of the plan, is generally mandated by individual states versus the federal government, so it’s unknown what the plan will mean for each state, according to Chicagoland-based lifecare manager Patricia Cline.

However, family caregivers should keep their eyes on the cost-saving concepts within the current draft. Here are three ways the plan’s proposals could potentially help you and your loved one save money on long-term care.

1. Expanded access to Medicaid programs could make home care more affordable

Medicaid covers 100% of basic nursing home stay costs in participating facilities. However, access to home care through Medicaid is much more limited and varies by state.

Biden’s plan proposes expanded access to two Medicaid programs aimed to help families afford at-home caregiving services, presumably with more funding and resources, though it is not explicitly stated:

-

Home and Community Based Services (HCBS): This is a waiver program that allows states the option to extend home- and community-based Medicaid services to needy individuals. People with severe injuries, intellectual disabilities and other debilitating conditions would have access to care, including homemaker (non-medical) or home health aide services, that will help them avoid nursing homes or facilities. Most states have an HCBS waiver, though they vary.

-

Money Follows the Person program: This is a federal program that launched in 2008 in order to enhance HCBS options in communities. It includes quality assurance measures over state HCBS programs and grant awards for states looking to broaden their offerings.

The proposal currently only applies to those who qualify for Medicaid. Typically, those who qualify for Medicaid fall under a designated household income cap and are considered low-income. Eligibility, however, varies widely depending on the applicant’s state.

What experts say: The concept of expanding Medicaid at-home programs is a step in the right direction, making it possible for more older Americans to age in place, according to Bernard A. Krooks, founding partner of the New York City-based law firm Littman Krooks LLP.

Krooks, however, is curious to see whether future drafts of the plan will include middle class families who don’t qualify for Medicaid. “They are going to need more and more help as the Baby Boomer population gets older,” he notes. “We need to make home care more accessible to them.”

A widely used Pew Research study defines middle class households as earning between 67% and 200% of the median household income. According to the latest available Census Bureau numbers, this translates to earning anywhere between $45,802 and $137,406 annually, an amount made by almost half of the U.S. population.

2. Better pay for caregivers and more affordable, high-quality care for seniors

The proposal focuses heavily on caregiver worker rights, noting that paid caregivers are “underpaid” and “undervalued,” earning approximately $12 an hour and disproportionately living in poverty. It proposes the creation of middle-class jobs and the choice for these workers to join unions. At the moment, this language only refers to home health aides who work for agencies and institutions that accept Medicaid, and so the extra funds would ostensibly come from the government, not the patients.

What experts say: Improved worker conditions, such as higher wages and the ability to join a union, could potentially lead to higher-quality, affordable care for seniors on Medicaid.

“If we start paying [caregivers] a fair wage, the overall quality of care people get will improve,” says Krooks.

After all, when caregivers are compensated properly, they’ll have more resources to invest in continuing education, transportation capabilities and their own health and well-being.

There is also a shortage of home health workers in a time of increasing demand, which raises the cost of home care. The latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics found that skilled nursing and homemaker service jobs were expected to increase by 34% from 2019 to 2029 — much faster than the average (7%) for all occupations. As of 2019, 4.4 million more home workers will be needed to meet demand in the ensuing years.

That said, making the job more attractive is critical for workers and families alike, according to Ric Edelman, founder of the national firm Edelman Financial Engines. If professional caregiving becomes a more attractive career path — thanks to increased compensation and access to pay-bolstering education — more people will pursue it, and families in need of aid will have their choice of even more talented caregivers.

3. Medicaid coverage when you need it

The plan briefly mentions that families often have to wait years to receive certain Medicaid benefits even if they qualify. The HCBS waiver, for example, is considered optional rather than a part of basic care. Therefore, states can limit enrollment and place applicants on long waiting lists.

Krooks even says that patients often die before they receive these benefits. However, whether or not the finalized plan will address this precise issue is unknown. One possibility: The federal government could ease the wait for older adults by making programs like HCBS a part of basic care.

What experts say: “I’m very interested to know how specifically they are going to get the waiting list down,” says Cline, who recently served a client who waited almost two years to receive benefits. “But there is a lot of potential in the proposal, and it starts the conversation.”

What comes next

It remains to be seen how this plan will take shape and ultimately offer savings for older adults and family caregivers. It could take months of congressional deliberation before the plan is filled out with details and finalized.

But there’s undoubtedly an intense and growing need to tackle the country’s care crisis head-on. As Edelman points out, our nation is overdue in acknowledging the challenges faced by caregivers and older adults.